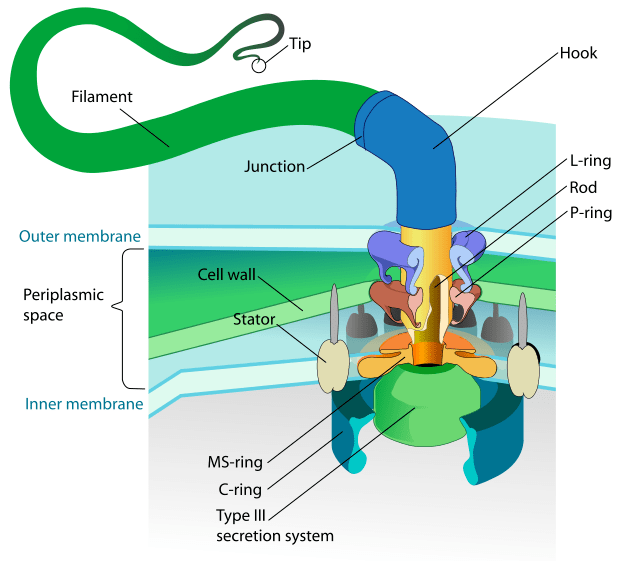

As creationists, we are all familiar with irreducible complexity, or at least have a broad understanding of it. The two classic examples of irreducible complexity are a mousetrap (a man-made object) and a bacterial flagellum (a design occurring in nature). The essence of irreducible complexity is that a system performs a distinct function, the system is composed of multiple parts, and the removal of any part with render the entire system functionless. A mousetrap has a purpose: to catch mice. To function, it needs a hammer, a spring, a latch, and a catch, to name a few parts. Remove any one of those pieces, and the entire mousetrap fails to function. Similarly, a bacterial flagellum consists of a rotor (the MS-ring in the illustration above), a stator, and a hook. Remove any one of those parts, and the entire flagellum fails to function.

Irreducibly complex structures in biological organisms are used as evidence for a designer. After all, if we recognize that the mousetrap was designed by a person, then should we not also recognize the bacterial flagellum as the product of a person (namely, God)?

It should be no surprise that irreducible complexity has come under scrutiny by evolutionists. After all, irreducible complexity was created specifically as a challenge for Darwin’s theory of evolution.[1] Those who accept the theory of evolution as true will naturally have an aversion to irreducible complexity.

One such evolutionist who wrote about irreducible complexity, and the intelligent design movement in general, is Niall Shanks. In fact, he wrote a book whose subtitle explains itself: God, the Devil, and Darwin: A Critique of Intelligent Design Theory.[2] Shanks’s book was first published in 2004, so it is 19 years old at this point. My intention is not to beat a dead horse. Instead, I ran across Shanks’s book for the second time recently, and there was a particular counter-example to irreducible complexity that he used that I thought was illuminating, so I wanted to talk about it.

Before we look at, and critique, Shanks’s counter-example, let us first be clear what is a counter-example. When used in formal logic, a counter-example is an example that runs contrary to a proposed universal idea. A counter-example is a very powerful type of argument, for if a counter-example exists, it proves that the proposed idea is false (or at least, is not true in all circumstances, which in logic, is the same thing as saying that a universal idea is false). Thus, if Shanks is correct in his counter-example, he effectively nullifies irreducible complexity. Now that we know what is at stake, let us examine Shanks’s counter-example.

Shanks’s example is the Belousov-Zhabotinski reaction (BZ reaction). This is a reaction that Shanks has used several times in the classroom, demonstrating it in front of his students. Shanks uses potassium bromate, malonic acid, potassium bromide, cerium ammonium nitrate, and sulfuric acid.[3] The interaction of these chemicals is rather complex, but the effect, and general description, is rather simple. The chemical reactions repeatedly fluctuate between two endpoints. One endpoint of the reaction is clear, the other is yellow. In other words, if you were to watch a beaker in which these chemicals have been mixed, the beaker will start as clear, then it will change to yellow, then change back to clear, then back to yellow, and on and on. This cyclic reaction can continue for more than an hour.

Now comes the crux of Shanks’s argument. The BZ reaction is an example of irreducible complexity.[4] The reaction has a purpose. Or at least, it can. The regular oscillation back and forth can used to record time, in a similar manner to the ticking of a clock. In fact, old clocks, like a grandfather clock, keep time using an oscillating mechanism (a pendulum). There are five components (chemicals) needed in the reaction, and if any one of them is absent, then the visible oscillations do not occur. I tend to agree with Shanks, the BZ reaction is irreducibly complex, if it is intentionally used in timekeeping. Shanks triumphantly notes that “The explanation of this behavior [oscillations of the BZ reaction] does not require the intervention of a supernatural intelligence.”[5]

Now, the fact that Shanks identified the intelligence as supernatural is irrelevant. When design is detected by means such as irreducible complexity, it is done irrelevant of knowledge of who or what the designer is.[6] Thus, when we observe irreducible complexity in a thing, it only follows that the thing was designed by something: the designer need not necessarily be supernatural. Thus, to streamline Shanks’s statement, let us drop the “supernatural” part, and simplify it to “The explanation of this behavior does not require the intervention of an intelligence.”

I want you to stop and ponder that statement a moment. Niall Shanks, a university professor, puts together a demonstration for his students, and concludes that the demonstration “does not require the intervention of an intelligence.” Do you note the contradiction? Shanks sets up the BZ reaction for his students, yet he says that the BZ reaction occurs without intervention of an intelligence. Either Shanks is admitting that he is unintelligent or he has forgotten that the components of the BZ reaction were put into the beaker on purpose by himself.

I would say that Shanks’s demonstration is a failed counter-example to irreducible complexity. Quite the opposite, since he, an intelligent human being, put the reaction together, I think the BZ reaction is consistent with the conclusion that irreducibly complex things are the result of an intelligence.

At this point, Shanks has one of two options. His first option is to admit defeat and acknowledge that the BZ reaction is not a counter-example to irreducible complexity. The second option is to somehow deny that his involvement in the BZ reaction constitutes intelligent design. There are various ways Shanks may claim that he is not responsible for the BZ reaction. He may claim that he, and his actions, are simply the result of chemical reactions occurring within his brain. In other words, he is not an elective agent, but is a reactionary machine, responding to his environment.

That latter option seems rather bleak, doesn’t it? Are people mere automatons, a bag of incredibly complex reactions responding to the environment? As bleak as it may seem, it would allow someone like Shanks to claim that the BZ reaction was not created using intelligence. The problem with such an argument is: no one really believes it. Even if someone where to insist that his actions are merely the result of physical laws, I know that person does not truly believe it. How? If that person wrote something, he would demand credit for it. Again, take Shanks as an example. He wrote God, the Devil, and Darwin. He is listed as the author. He wants people to know he is the author so he can receive credit for it. If someone else copies with work without attribution, he would be upset, and claim that the person stole his words or idea. In other words, Shanks acts as if his work is his own: he possesses it because he created it. But once he admits that he created his own work, he admits that he is a creator, and that there is intelligence in the world. After all, automatons do not receive credit for the work that they do: they simply perform predetermined tasks.

Now, as far as I know, Shanks has not argued that he, or any other person, is an automaton. However, I wanted to illustrate that, even if the argument were made, people do not behave as if they are automatons, they behave as if they are human beings who are responsible for the things that they create. Humans as mere reactive agents is not an option that people take seriously. Thus, if we return to the BZ reaction, Shanks must have overlooked the fact that he, an intelligent agent, created the BZ reaction, an irreducibly complex system. His whole argument is rendered moot because he apparently failed to understand the point of the argument.

In my experience, many arguments against intelligent design fall into the same problem as Shanks’s BZ reaction. Their counter-examples miss the point or overlook the rather simple fact that they themselves are intelligent agents (little creators, if you will).

Thoughts from Steven

[1]Behe, Michael (1996) Darwin’s Black Box: The Biochemical Challenge to Evolution Touchstone, New York, New York, pg. 39-40

[2]Shanks, Niall (2004) God, the Devil, and Darwin: A Critique of Intelligent Design Theory Oxford University Press, Oxford, England

[3]Ibid. pg. 176-178

[4]Ibid. pg. 178

[5]Ibid. pg. 178

[6]Behe, Michael (1996) Darwin’s Black Box: The Biochemical Challenge to Evolution Touchstone, New York, New York, pg.196-198