On June 12, 1983, Owen Burnham and his family happened upon the carcass of a peculiar sea creature. At the time, the Burnham family lived in Sengal, but on this day, they were vacationing in Gamiba.[1] The creature that they saw has since been called “Gambo,” and it has become a rather famous case in crytozoology.

Cryptozoology is the study of “hidden” animals. That is, it is the study of animals whose existence has not been accepted or confirmed. Think bigfoot, Loch Ness monster, and yeti as examples of creatures that are studied by cryptozoology. Cryptozoology is regarded as a pseudoscience as it is largely based on occasional, unconfirmed sightings of unknown creatures. After all, if a body could be produced, if a specimen could be caught, the animal would be described and published in a scientific journal and it would not be unknown anymore. The very fact that cryptozoology studies creatures with no physical remains (barring footprint casts, a few stray hairs, and blurry photographs) pretty much means that cryptozoology will always remain an unaccepted field of study. After all, scientists want something physical, something that anybody can see and study, to be the basis of a new species. That is why type specimens are so important.

A type specimen is the original specimen that is used to define a new species. If a scientist thinks he has found a new species of field mouse, for example, he needs a specimen that he can designate as the type specimen, the definition of the anatomy of the new species. That type specimen then gets preserved in a museum so that if another scientist wants to study this new species, compare it to existing species, or even challenge its designation as a new species, he can go and study the type specimen himself.

Part of the purpose of type specimens is to ensure that mistakes are not made in the identification of a new species. If a scientist reads the description of a new species and thinks that the description sounds wrong, incorrect, or just a little fishy, he can visit the type specimen and check the description himself. Such has happened in the past. For example, the lizard species Anolis isthmicus was found to be the same as the species Anolis boulengerianus. How was the fact that they are the same species confirmed? By comparing type specimens.[2]

Turning the discussion back to Gambo, the main reason it is so special is because the body of this mysterious sea creature was largely intact. Most other mysterious bodies that are washed ashore are typically in a high state of decomposition, which complicates their identification. Let me give an example. There is a rather common phenomena called a pseudoplesiosaur. This occurs when the body of a basking shark decomposes and, during the decomposition process, takes on the (very rough) appearance of a plesiosaur. As the shark decomposes, the jaws and gills, which are rather loosely attached to the rest of the body, fall off, leaving the braincase attached to the end of the spinal column, which gives the appearance of a long neck with a small head. The lower fluke on the tail can decay away, leaving a straight, featureless tail. Similarly, the dorsal fins can decay away. A general state of decay obscures other details, leaving the general appearance of a large sea creature with four fins, a long neck and small head, and a pointed tail. In other words, roughly like most people’s idea of a plesiosaur.

The most famous example of a pseudoplesiosaur is the Zuiyo Maru carcass. The Zuiyo Maru was a Japanese fishing vessel that dredged up a mysterious carcass off of New Zealand in 1977. While some considered it to be the remains of recently dead plesiosaur, chemical analysis of horny fibers taken from the carcass proved to be nearly identical to elastoidin, a protein unique to sharks.[3]

If the idea of a pseudoplesiosaur sounds incredible, understand that this phenomena is widely acknowledged by cryptozoologists.[4] Keep in mind, these cryptozoologists are willing to consider the possibility that extinct creatures have survived into modern times. If they admit that a basking shark carcass can decay to look like a plesiosaur, they are not doing so because “official science demands” that these plesiosaur carcasses get explained away. They actually considered various options and decided that the pseudoplesiosaur explanation is best for most of these carcasses.

Which brings us back to Gambo. Unlike a pseudoplesiosaur, Gambo was not found in a state of decomposition. It had the appearance of being recently deceased. Thus, Gambo is sometimes given as a counter-example to the claim that all sea serpent bodies that are washed ashore are misidentified because they are in an advanced state of decomposition.[5] Having such a carcass is not as good as having a type specimen, but at least it can be treated with more certainty than a pseuodoplesiosaur, right?

To investigate just how well the description of Gambo holds up, I want to give an extensive quote. This quote is a compilation of letters sent from Owen Burnham to Karl Shuker. Shuker is a prominent person in the cryptozoology community. Of important note is that Shuker was the first cryptozoologist to publish an article about Gambo in 1986.[6] In other words, this information Shuker compiled about his correspondence with Burnham is as close to primary information as we can get without interviewing Burnham ourselves. I want to quote this compilation in its entirety, because there is a lot of information about Gambo and how it was observed that needs to be teased out. Here is the compilation. I have made no alterations or comments to the following quote. It is exactly as given in the source material:

I grew up in Senegal (West Africa) and am an honorary member of the Mandinka tribe. I speak the language fluently and this greatly helped me in getting around. I’m very interested in all forms of life and make copious observations on anything unusual.

In the neighbouring country of Gambia we often went on holiday and it was on one such event that I found this remarkable animal.

June 1983. An enormous animal was washed up on the beach during the night and this morning [June 12] at 8.30 am I, my brother and sister and father discovered two Africans trying to sever its head so as to sell the skull to tourists. The site of the discovery was on the beach below Bungalow Beach Hotel. The only river of any significance in the area is the Gambia river. We measured the animal by first drawing a line in the sand alongside the creature then measuring with a tape measure. The flippers and head were measured individually and I counted the teeth [In the sketches accompanying his description, Burnham provided the following measurements: Total Length = 15-16 ft; Head+Body Length = 10 ft, Tail Length = 4½ -5 ft; snout length = 1½ ft; Flipper Length = 1½ ft.]

The creature was brown above and white below (to midway down the tail).

The jaws were long and thin with eighty teeth evenly distributed. They were similar in shape to a barracuda’s but whiter and thicker (also very sharp). All the teeth were uniform. The animal’s jaws were very tightly closed and it was a job to prise them apart.

The jaws were longer than a dolphin’s. There was no sign of any blowhole but there were what appeared to be two nostrils at the end of the snout. The creature can’t have been dead for long because its eyes were clearly visible and brown although I don’t know if this was due to death. (They weren’t protruding). The forehead was domed though not excessively. (No ears).

The animal was foul smelling but not falling apart. I’ve seen dolphins in a similar state after five days (after death) so I estimate it had been dead that long.

The skin surface was smooth, the only area of damage was where one of the flippers (hind) had been ripped off. A large piece of skin was loose. There were no mammary glands present and any male organs were too damaged to be recognizable. The other flipper (hind) was damaged but not too badly. I couldn’t see any bones.

I must mention clearly that the animal wasn’t falling apart and the only damage was in the area (above) I just mentioned. The only organs I saw were some intestines from the damaged area.

The paddles were round and solid. There were no toes, claws or nails. The body of the creature was distended by gas so I would imagine it to be more streamlined in life. It wasn’t noticeably flattened. The tail was rounded [in cross-section], not quite triangular.

I didn’t (unfortunately) have a camera with me at the time so I made the most detailed observations I could. It was a real shock. I couldn’t believe this creature was laying in front of me. I didn’t have a chance to collect the head because some Africans came and took the head (to keep skull) to sell to tourists at an exorbitant price. I almost bought it but didn’t know how I’d get it to England. The vertebrae were very thick and the flesh dark red (like beef). It took the men twenty minutes of hacking with a machete to sever it.

I asked the men on the scene what the name of this animal was. They were from a fishing community and gave me the Mandinka name kunthum belein. I asked around in many villages along the coast, notably Kap Skirring in Senegal where I once saw a dolphin’s head for sale. The name means ‘cutting jaws’ and is the term for dolphin everywhere. Although I gave good descriptions to native fishermen they said they had never seen it. The name kunthum belein always gave [elicited] a dolphin for reply and drawings they made were clearly that. I also asked at Kouniara, a fishing village further up the Casamance river but with no success. I can only assume that the butchers called it by that name due to superficial similarities. In Mandinka, similar or unknown animals are given the name of a well known one. For example a serval is called a little leopard. So it obviously wasn’t common. I’ve been on the coast many times and have never seen anything like it again.

I wrote to various authorities. [One] said it was probably a dolphin whose flukes had worn off in the water. This doesn’t explain the long pointed tail or lack of dorsal fin (or damage).

[Another] decided it could be the rare Tasmacetus shepherdi whose tail flukes had worn off. This man mentioned that the blow hole could have closed after death. Again the tail and narrow jaws seem to conflict with this. Tasmacetus‘s jaws aren’t too long and the head itself seems to be smaller than my animal’s. Tasmacetus has two fore flippers and none in the pelvic region. The two flippers are quite small in relation to body size and pointed rather than round. Tasmacetus has a dorsal fin and ‘my’ animal didn’t seem to have one or any signs of one having once been there. Tasmacetus even without tail flukes wouldn’t have a tail long enough or pointed enough. The tail of the animal I saw was very long. I had a definite point and didn’t look suited for a pair of flukes. Apparently, Tasmacetus is brown above and white below and this seems to be the only link between the two animals. I’ve been to many remote and also popular fishing areas in Senegal and I have seen the decomposing remains of sharks and also dead dolphins and this was so different.

[A third] said it must have been a manatee. I’ve seen them and believe me it wasn’t that. The skin thickness was the same but the resemblance ended there.

Other authorities have suggested crocodiles and such things but as you see from the description it just can’t have been.

After I think of the coelacanth I don’t like to think what could be at the bottom of the sea. What about the shark (Megachasma) [megamouth shark] which was fished up on an anchor in 1976?

I looked through encyclopedias and every book I could lay hands on eventually I found a photo of a skull of Kronosaurus queenlandicus which is the nearest thing so far. Unfortunately the skull of that beast is apparently ten feel long and clearly not of my find.

The skeleton of Ichthyosaurus (not head) is quite similar if you imagine the fleshed animal with a pointed tail instead of flukes. I spend hours at the Natural History Museum [in London, England] looking at their small plesiosaurs, many of which are similar.

I’m not looking to find a prehistoric animal, only to try and identify what was the strangest thing I’ll ever see. Even now I can remember every minute detail of it. To see such a thing was awesome.[7]

On the surface, Burnham’s testimony sounds compelling. After all, he presents himself as a man who is careful with details. He made detailed observations of the animal when he saw it, had seen dead bodies of dolphins before so he had something to compare it to, followed up on the name given to him by the natives, and did his own research after experts failed to properly identify the creature. Surely his observations and testimony are reliable, trustworthy, and accurate.

Right?

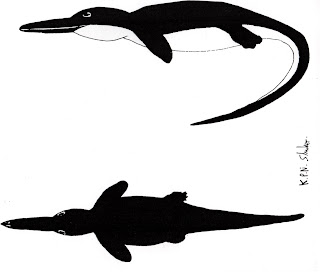

The first important thing to note about Burnham’s account is the time gap between seeing the animal and his description of the animal. The sighting took place in June 1983 while his correspondence with Shuker took place between May and July 1986.[8] Along with that, note that Burnham makes no mention of sketching the animal or writing down its description while he was observing it. He notes he had no camera so he “made the most detailed observations [he] could.” Now, Burnham did provide a sketch of Gambo,[9] but without any assurance that this sketch was made on site at the time he observed the creature, then for all we know, the sketch was made three years after his observations. Thus, we appear to be relying on Brunham’s memory and his memory alone for all the details of Gambo.

Now, some people may say, “What’s the problem? Some people have excellent memory. Perhaps Burnham is one of those people.” That’s the problem, isn’t it? Perhaps he is a person with excellent memory, or perhaps he is not. No proof of his memory abilities is provided, so we just have to trust that he gave the correct information.

We can check his account against his drawing to see if all his details are consistent. As it turns out, they are not. Notice in his drawing, he gives Gambo pointed fore flippers, yet in his description, he notes that the “paddles were round and solid.” Which is it? Are the paddles pointed, like his sketch, or where they round, like his description?

He also noted that one of the hind flippers was missing, along with a large flap of skin loose in that area. Yet, his sketch shows no such damage. Now, this is not necessarily an error: he probably reconstructed what he imagined the missing flipper looked like, rather than showing the damage. Yet, that lends itself to another problem: his sketch, at least, is his impression of what the whole animal looked like, not a detailed sketch of the body as he saw it. If he made a meticulous sketch of the body as he saw it lying on the beach, it would include every detail, including the damaged area. It should also be pointed out that he gave no indication of the size of the damaged area. Thus, we do not even know how much of his sketch is reconstruction versus actual observation.

Regarding the damage, Burnham emphasized that the missing flipper was the only damage. He said that “the only damage was in the area [he] just mentioned.” Yet, based on his own account, we know that cannot be the case. Why? Because Burnham said that he and his family “discovered two Africans trying to sever its head so as to sell the skull to tourists.” If these men were trying to sever its head, then surely there were already hack marks on the head or neck before the Burnhams arrived. Yet, once again, no hack marks are seen on the sketch.

The fact that these men were cutting off the head raises another question: how accurate are Burnham’s observations of the head and neck? Did he measure the length of the head before or after it had been hacked? Did the hacking cut off chunks of flesh, shortening the neck? Was the head pulled and yanked during the hacking, stretching the head? Did flaps of skin from the hacking distort the head and neck’s appearance? We do not know, because Burnham did not describe the hacking of the head other than to mention that it happened. Thus, we really cannot be sure about much of the description of the head and its size. And yet, the size of the head was one of the reasons Burnham discounted the Tasmacetus identification. Without accurate measurements of the head, how can we be sure that the head of Tasmacetus is really too small to be Gambo?

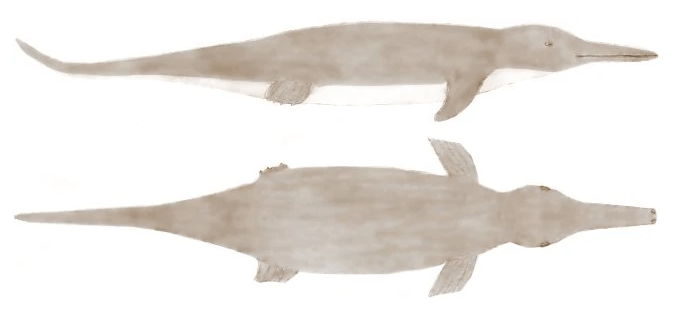

Since it has been brought up, I want to explain what Tasmacetus is. This is the generic name of Sheperd’s beaked whale. This is a rare whale that looks superficially like a dolphin. It was only named in 1937, and as of 2006, there had only been 42 records of this whale washed ashore and five records of it being seen alive.[10] Since it is rare, it is unfamiliar, which is probably part of the reason it was suggested as the identity of Gambo, in addition to its coloration.

I want to address Burnham’s critiques of the various suggestions given to him by experts, including the idea that Gambo was a Tasmacetus specimen. However, I want to first assure my readers that, despite my critiques of Burnham’s account, I am not accusing him of being a liar. It is easy to presume that finding contradictions in an account means that the person giving the account is a liar. That is not my intent. For all I know, Burnham is perfectly honest and would never lie. However, I am suggesting that his memory is fallible. That is the issue here. No matter how perfect the body of Gambo, no matter how good Burnham’s observations, we must still rely on the memory of Burnham for the entirety of our knowledge of Gambo.

If any part of Burnham’s memory is incorrect, then we will fail to properly identify Gambo. For example, just as Burnham claimed, Shepherd’s beaked whale has pointed flippers, unlike his description of Gambo. However, it is like his sketch of Gambo. If the sketch is more accurate than his description, Gambo is one step closer to being identified as Tasmacetus.

What of the dorsal fin and flukes? The beaked whale has them but Gambo does not. Burnham assures us that there was no sign of a dorsal fin or a mark where the fin should be. However, he did say that his “animal didn’t seem to have [a fin] or any signs of one having once been there.” “Didn’t seem” is not very good assurance. Could it be that Burnham overlooked a detail? After all, he didn’t appear to consider the Tasmacetus possibility until it was suggested by an expert. Did he know where to look for a fin on a Tasmacetus body? If he wasn’t looking for a fin in its appropriate location, how can we know that there really was not mark or remnants of a fin? Surely we have all had those instances where we overlook a detail until it is pointed out to us, and then we can never overlook the detail again. Maybe a detail was obvious all along, but because he didn’t know to look for it, Burnham overlooked it.

I know I am being picky, highlighting ever detail and questioning every claim. It would be easy to settle my questions: have a body to examine. That is why it is such a shame that Burnham let the head of Gambo get away. With no body, with not a single piece from the body, it is impossible to verify any part of Burnham’s recollections. When he decided not to buy the head, he doomed Gambo to remain a mystery.

This has been a long post, but I think the length was necessary. it is easy to take a person at his word without any sort of verification. If it is a trusted friend and he is talking about a common occurrence, verification is not necessary. However, if it is a matter of a brand new species of animal, verification is essential. That is why biologists are so picky about type specimens. Without a body, there is no way to tell whether a mystery creature is or is not a known species.

So what was Gambo? The truth is, we will never know. And that is okay. We must come to grips with the fact that there are events that happened in the past that can never be verified. We cannot go back and examine the body of Gambo with Owen Burnham. Whatever that creature was, it is lost to history, forever to remain a mystery. Any speculation about its identity is just that: speculation. And speculation is not good enough to support the claim that Gambo is a distinct creature unlike anything else known to science.

Thoughts from Steven

[1]Shuker, Karl (1995) In Search of Prehistoric Survivors: Do Giant ‘Extinct’ Creatures Still Exist? Blandford, London, England, pg. 116

[2]Nieto-Montes de Oca, Adrián; Gunther Köhler; and Manuel Feria-Ortiz (2014) “Anolis boulengerianus Thominot, 1887, a senior synonym of Anolis ishthmicus Fitch 1978 (Squamata: Dactyloidae)” Zootaxa 3794(1): 125-133

[3]Kimura, Shigeru; Katsuyuki Fujii; Hajime Sato; Sueshige Seta; and Minoru Kubota (1978) “The Morphology and Chemical Composition of Horny Fiber from an Unidentified Creature Captured off the Coast of New Zealand” in Collected Papers on the Carcass of an Unidentified Animal Trawled off New Zealand by the Zuiyo-maru La Société franco-japonaise d’océanographie, Tokyo, Japan, pg. 67-74

[4]Shuker, Karl (1995) In Search of Prehistoric Survivors: Do Giant ‘Extinct’ Creatures Still Exist? Blandford, London, England, pg. 98-99 and Newton, Michael (2005) Encyclopedia of Cryptozoology: A Global Guide McFarland & Company, Jefferson, North Carolina, pg. 175

[5]Shuker, Karl (1995) In Search of Prehistoric Survivors: Do Giant ‘Extinct’ Creatures Still Exist? Blandford, London, England, pg. 118

[6]Shuker, Karl (2019) “Gambo, the Gambian sea serpent – or, how a very mysterious stranger on the shore launched my cryptozoological career” shukernature, retrieved from https://karlshuker.blogspot.com/2019/05/Gambo-gambian-sea-serpent-or-how-veryu.html?m=1 on January 6, 2024

[7]Shuker, Karl (1995) In Search of Prehistoric Survivors: Do Giant ‘Extinct’ Creatures Still Exist? Blandford, London, England, pg. 116-118

[8]Ibid. pg. 116

[9]Cryptid Wiki (date unknown) “Gambo” Cryptid Wiki retrieved from https://cryptidz.fandom.com/wiki/Gambo on January 6, 2024

[10]Pitman, Robert; Anton van Helden; Peter Best; and A. Tony Pym (2006) “Sheperd’s beaked whale (Tasmacetus shepherdi): Information on appearance and biology based on standings and at-sea observations” Marine Mammal Science 22(3): 744-755