In my last post, I talked about “build a better body” thought experiments. While these experiments focus on different “problems” in the human body and come up with a variety of “solutions,” one “flaw” that is almost universally addressed is the backwards human retina.

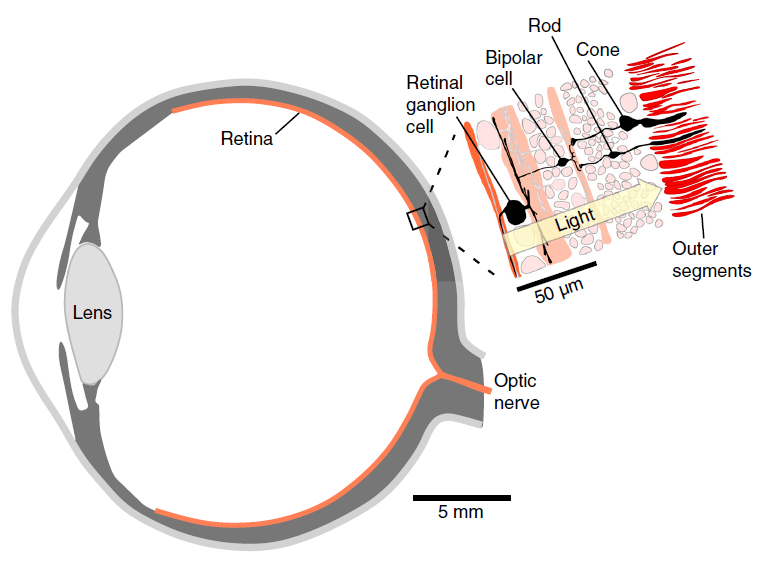

Technically, the backwards human retina is called an inverted retina. The retina is the part of the eye that contains the photoreceptors: the sensory cells specialized for detecting light. There are two types of photoreceptors: rods and cones. Rods are more sensitive to light but only perceive light versus dark (black and white) while cones require more light but can perceive different colors. The photoreceptors form a single layer at the back of the retina. In humans, and in all vertebrates, for that matter, there are two more layers of cells within the retina: two layers of neurons (nerve cells) extend from and lie on top of the photoreceptors. It is important to note that these neurons have a purpose: they are responsible for processing sight information. That’s right: we actually begin processing and interpreting information from the photoreceptors before that information even leaves the eye. Eventually, these neurons join to form a single nerve, the optic nerve, which then exits the eye and connects to the brain.

At a glance, the human eye appears to be backwards. The photoreceptors are located at the back of the retina with the two layers of neurons lying on top of the photoreceptors. That means the incoming light has to pass through two layers of cells before reaching the light sensitive receptors. That is why the human retina, and the retina of all vertebrates, is called inverted: the neurons and photoreceptors are in the reverse order of what we expect them to be.

Interestingly, there is an example of a human-like eye where the retina is everted, that is, the photoreceptors are in front and the neurons are in the back. This type of eye is found in the cephalopods, the group of mollusks that includes the octopuses and squids.

Why do humans and vertebrates have an inverted eye while cephalopods have an everted eye? The evolutionary explanation is that, during the development of the vertebrate neural tissue, the receptor surface got “stuck” on the inside of the nervous system. During embryonic development, the nervous system of a vertebrate starts as a plate that grows along the back of the embryo. This plate then folds over on itself, creating a long tube. The photoreceptors develop from the inside of this tube. Thus, when the eyes are formed by budding off of the nervous system, the outside of the neural tube becomes the front of the eye and the inside, where the photoreceptors are found, wind up at the back of the eye.i

In my previous post, I mentioned the concept of evolutionary precedent. That is the idea that the body plan of an ancestor constrains the body plan of its descendants. The inverted retina of vertebrates is thought of as one such constraint: because the vertebrate nervous system developed as a plate that folds into a tube, vertebrates are “stuck” with an inverted retina. Thus, those who partake in “build a better body” experiments almost always want to correct this evolutionary flaw. After all, cephalopods have a proper, everted retina, so there is no reason why an ideal human body should be saddled with a backwards retina, right?

Before I answer this question, I want to point out that this view of the inverted retina is limited. It is our impression, and our impression only, that tells us that the human retina is backwards. Surely we have all encountered situations where our earliest impression tells us things should be one way, only for more information to change our conclusion. In a murder mystery, the person standing over the body of the victim isn’t the murder, as it first appears: he is an innocent friend who happened to find the body. The whole point of the story is that the detective has to carefully uncover every fact to reveal who the true murder is. We have to take a similar approach with science: first impressions are not always correct, and we must be careful to uncover every piece of information before deciding that a particular design is flawed or imperfect.

Here is where a creationist’s perspective will differ from that of an evolutionist’s. While an evolutionist believes that the human body is a hodgepodge of designs thrown together over the course of millions of years, a creationist believes that the human body was created by God. As creationists, we inherently believe that God created humans with a very good body, so if a design appears backwards to us, we trust that it only appears backwards and that further investigation may reveal God’s intention in the “backwards” design.

The first clue that the human eye may not be flawed is the fact that all vertebrates have an inverted retina. Did God bungle the design of the vertebrate eye over and over again with each new kind He created? Not likely. In fact, there is an interesting counter-example found among vertebrates. Some reptiles and amphibians have a third eye. Called the pineal eye, it is found on top of the head and it is usually covered by skin. Unlike the paired eyes, the pineal eye does not form an image. It appears that the purpose of the pineal eye is simply to detect brightness in order for the animal to gauge the time of day to regulate its daily cycles. Despite having a different function, the pineal eye still has a retina, and the retina of the pineal eye is everted.ii Despite the fact that vertebrate eyes are supposedly inverted because the retina got stuck on the wrong side of the neural tube, the pineal eye demonstrates that vertebrate retinas do not have to be inverted. Which suggests that the inverted retina is purposeful and not the result of a constraint.

The second thing to note is that even though the retina has two layers of neurons in front of the photoreceptors, the retina is designed so that incoming light is distorted as little as possible. There are special cells in the retina called Müller cells that span the two layers of neurons. These cells appear to act as fiber optics, guiding light through the neurons, allowing the light to reach the photoreceptors with minimal distortion.iii Thus, the neurons do not pose a problem in the sense that the retina compensates for the layers of neurons, minimizing distortion. Put simply, human sight is not impaired by the neurons.

Interestingly, there is one part of the retina that lacks the two layers of neurons. This is the fovea centralis, and it is basically the center of the retina in the sense that it is the location where an image is focused.iv Since the fovea centralis is packed with the most perceptive photoreceptors in the retina, it provides the sharpest image possible. And it does not have the two layers of neurons to deal with. In other words, not only do the Müller cells help guide light through the neurons, the most sensitive part of the retina does not have the layers on top of it anyway. As we take these details into account, we start to see that the retina is not an accidental design: it is a complex structure suited for use.

We can still ask the question, why did God put the layers of neurons on top of the photoreceptors? I know of two suggestions why.v The first is that the two layers of neurons are necessary. They help process the image and reduce redundant information. The result is that by the time the information about the image reaches the optic nerve, the information has been compacted as much as possible. This results in a thinner optic nerve since it is carrying less information. In other words, these two layers of neurons actually improve the efficiency of the retina and optic nerve.

Now, these two layers of neurons have to be placed somewhere, either on top of the retina or behind the retina. Placing the neurons behind the retina would force the eye to be a little larger, taking up extra space, making the eye, and its associated structures, a little larger than it needs to be. In contrast, the area in front of the photoreceptors is already empty space: the camera-like structure of the eye requires an empty space between the lens and the photoreceptors. Why not use this already empty space to place the neurons, since the neurons already create minimal distortion of the image thanks the the Müller cells?vi In other words, putting the neuron layers in front of the photoreceptor cells makes the vertebrate eye more compact and efficient. Rather than being an accident of development, the vertebrate eye wastes as little space as possible while being as efficient as possible.

Another reason for putting the photoreceptors behind the neuron layers is simply because the photoreceptors are the most active part of the retina. They have to have a constant supply of nutrients in order to react quickly to changes in light in the image. The retina has no blood supply itself. Rather, blood is supplied to the eye through a layer called the choroid. The choroid lies behind the retina, which means that the photoreceptors, which are at the back of the retina, are adjacent to the blood supply.vii The photoreceptors are not at the back of the retina by a fluke of development: they are at the back of the retina so that they can most efficiently receive nutrients from the blood vessels in the choroid!

There is one more “flaw” of the human eye I want to address. That is the blind spot. Since the two neuron layers lie on top of the photoreceptors, when they join together to form the optic nerve, the optic nerve has to pass through the layer of photoreceptors in order to exit out the back of the eye. This spot where the optic nerve passes through the retina does not have any photoreceptors, which means our eyes cannot detect an image at that location. This blind spot, as it is called, is also cited as a flaw in the design of the human eye.

How many of you have noticed your blind spot? Do you go through your day with small objects disappearing from view because the image of the object happened to land on the blind spot? Certainly not. That alone should tell us that the blind spot is not a hindrance to our vision. However, to describe the trivial nature of the blind spot even more, recall that the fovea centralis is the center of our vision. It is where we see best, and any image that lies outside of the fovea centralis becomes part of our peripheral vision. Notice that when you glance around the room, you are aware of things lying in the periphery of your vision, but you only actually see and focus on what is in the center of your vision. Our eyes are not like a camera, which captures an image of everything in front of it: our eyes are designed to focus on the part of the image on our fovea centralis. And the blind spot lies far enough away from the fovea centralis that is cannot interfere with our sharp vision. Moreover, because our eyes have overlapping vision, one eye can see what is lying on the blind spot of the other eye. In other words, we don’t even miss details on the blind spot because the blind spot of our two eyes do not overlap! All in all, the blind spot does not affect our fine vision at the fovea centralis and our two eyes allow us to compensate for the blind spot in both eyes. There is no flaw here, either.

The inverted retina of the human eye is not some mistake or constraint due to a long process of evolution. Rather, if we consider the retina as a whole, the minimal distortion of an image due to the Müller cells, the efficiency of the eye due to the two layers of neurons, the efficient use of space placing the neurons in front of the photoreceptors, and the placement of the photoreceptors next to the blood supply in the choroid, the human eye is actually a marvel of engineering. A first glance may suggest to us that the retina is backwards, but a deeper understanding of its purpose and design actually leads us to conclude that is was created exactly as it was supposed to be.

As an aside, what about the poor cephalopods with their everted retinas? Do they have worse eyes because of it? Not really. While cephalopods have eyes that are similar to vertebrate eyes in many ways, are not vertebrate eyes. They simply have a different design. For example, cephalopods do not have a fovea centralis nor do they have the two layers of neurons to process information before it leaves the eye. Since its eye is constructed differently, we can presume that it functions differently as well. We can be assured that the Creator gave cephalopods exactly the type of eyes that they need, just as He gave us the type of eyes that we need.

Thoughts from Steven

i Rechenbach, A.; S. Agte; M. Francke; and K. Franze (2014) “How light traverses the inverted vertebrate retina: No flaw of nature” e-Neuroforum 5: 93-100

ii Ibid.

iii Ibid.

iv Ibid.

v To be fair, both of these suggestions come from evolutionists who were not looking for a purpose of God. However, they suggest reasons why the placement of the neurons is a beneficial design, and I simply interpret that beneficial design as an intentional design.

vi Baden, Tom and Dan-Eric Nilsson (2022) “Is our retina really upside down?” Current Biology 32: R300-R303

vii Rechenbach, A.; S. Agte; M. Francke; and K. Franze (2014) “How light traverses the inverted vertebrate retina: No flaw of nature” e-Neuroforum 5: 93-100